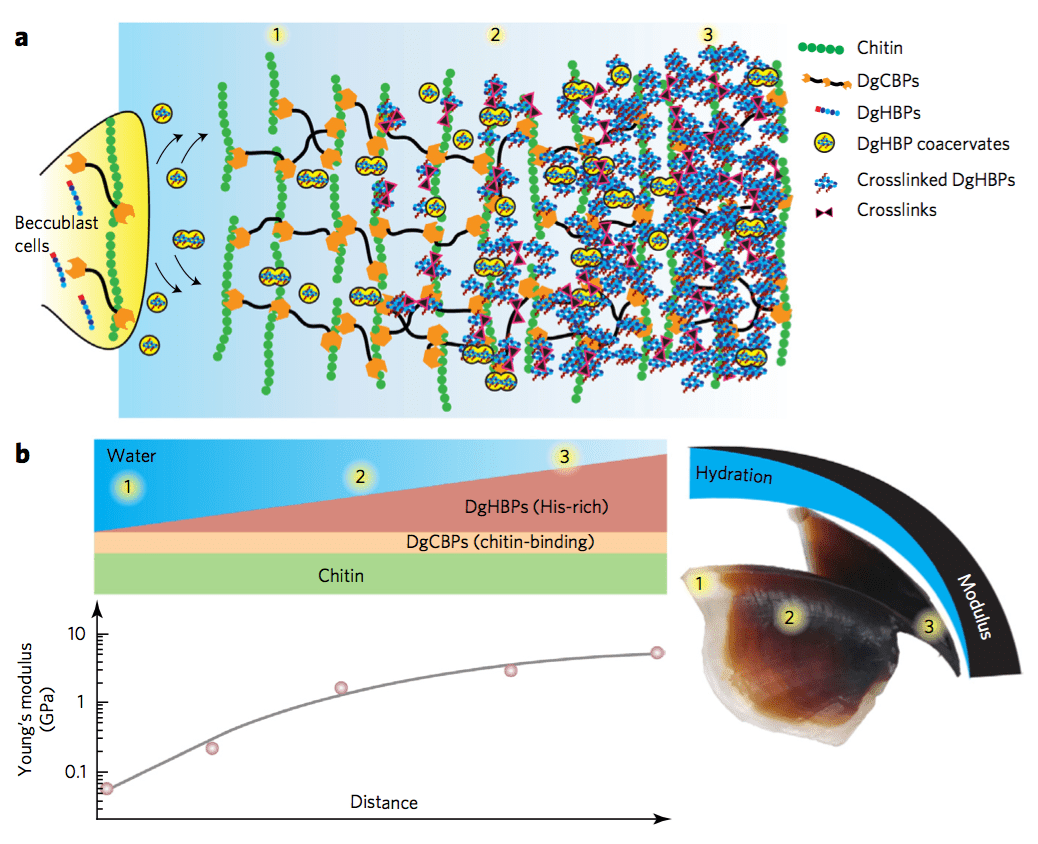

Minerals impart strength, stiffness, and wear resistance functionalities to biomaterials that assist in performing their mechanically active or supportive roles. In vertebrates, bones and teeth, composed of 70-90% of hydroxyapatite, are two classic examples. Recently, it has been recognized that in addition to using minerals, Nature also applies a contrasting strategy to make tissues with grinding or biting functionalities. For instance, studies highlight that in invertebrates’ jaws, strength and wear-resistance are achieved by metal ion cross-linking within a proteinaceous network. This involves dense protein cross-linking, and/or the formation of polysaccharide or protein complexes.

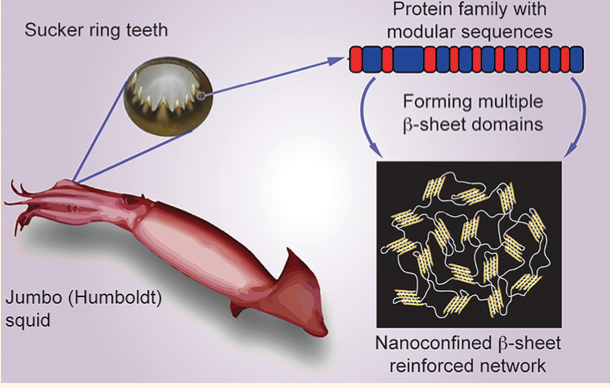

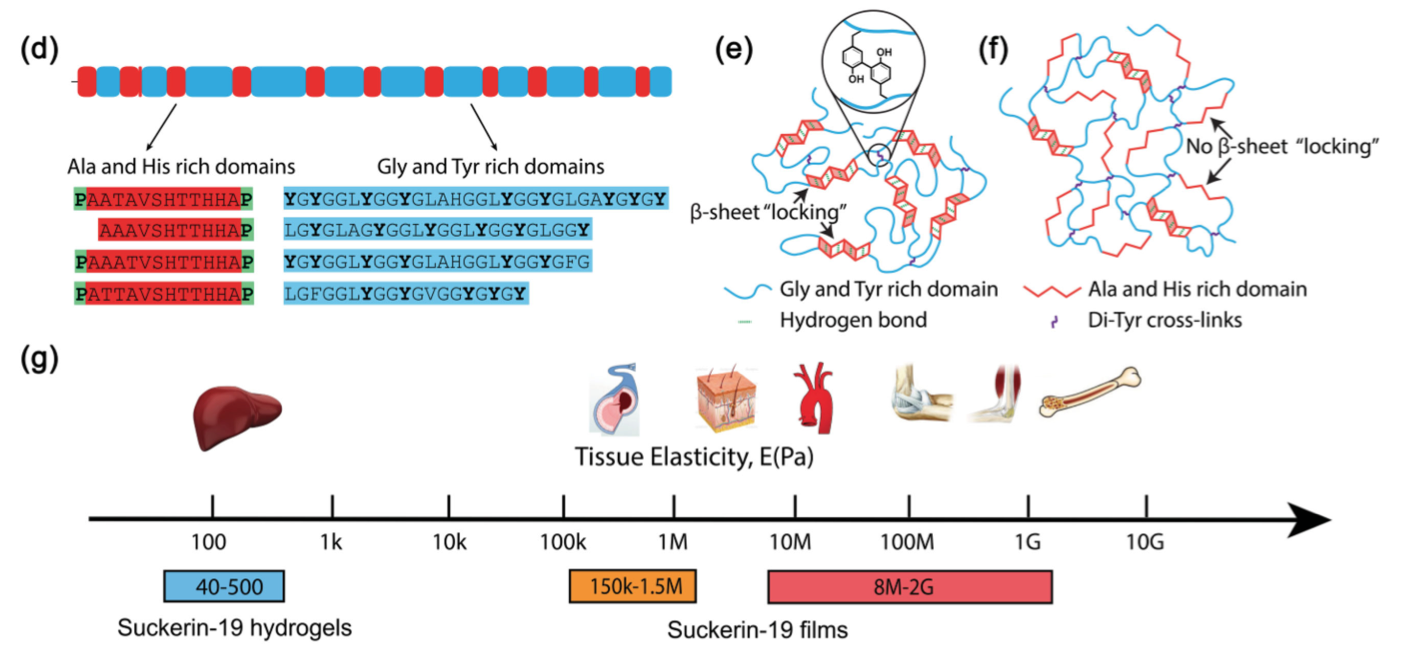

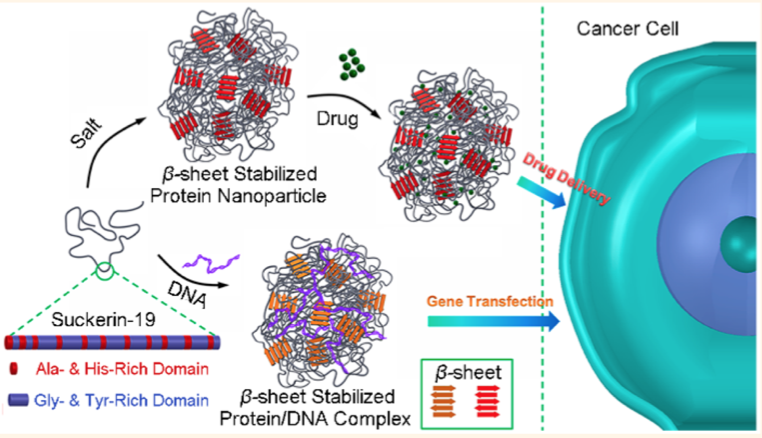

Such findings offer a novel paradigm for the biomimetic synthesis of robust and biocompatible structural polymers with little or no mineral content. These biomacromolecular networks feature remarkable mechanical performance twice in magnitude to that of the strongest synthetic polymers. In conjunction with that, their mechanical gradients can be controlled by a biomolecular gradient, which minimize interfacial stresses and confers the material with unrivaled abrasion resistance. In joint implants, wear and abrasion-resistance is a long-standing problem. Successful mimics of these organic networks can potentially be applied as restorative materials. Further, in the field of wear-resistant materials, the absence of minerals offers a new paradigm of research. Protein-based polymers also hold great potential to solve the growing sustainability issues associated with the production of polymers from fossil fuels (plastics) and their enormous accumulation in oceans and landfills (learn more).

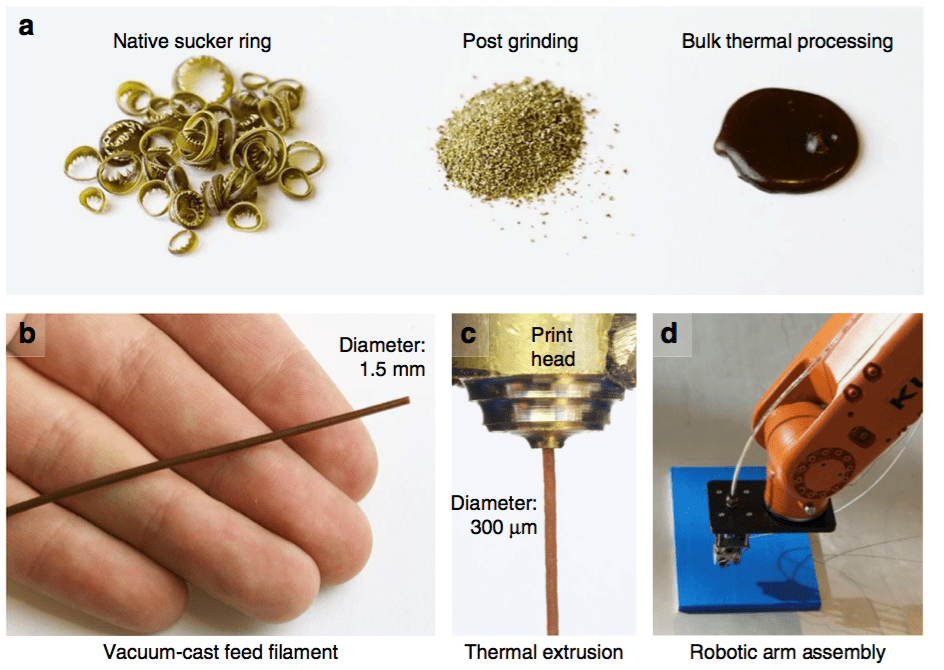

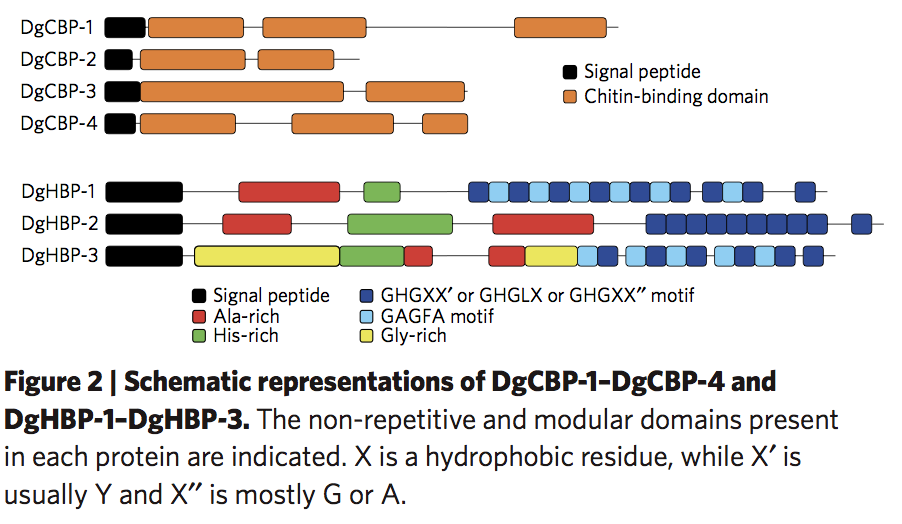

To synthesize such biopolymers, it is essential to understand their natural processing and the incorporation of building blocks (proteins, polysaccharides) into the final assembled tissue. Exploring these elusive features is necessary to duplicate Nature’s benign processing conditions/materials and constitutes a core aspect of our research.